The global challenges we face today — climate change, population growth, and the degradation of the natural environment — threaten not only our way of life, but the survival of our planet. To address these interconnected issues, we should start by looking at cities.

Today, the urban built environment accounts for about 70 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. Cities also consume the vast majority of our natural resources. What’s more, urban areas are growing — fast. Over 230 billion square meters of new urban development will be constructed worldwide over the next 40 years—the equivalent of adding a city the size of Paris to the planet every single week.

Instead of looking at rapid urban growth as a threat, we should consider it our best opportunity to save the planet. It’s a chance to reimagine the very nature of our cities from the ground up, and build a future that is more in balance with the Earth’s resources and ecosystems.

This places an enormous responsibility on those who shape the built environment: city planners, urban designers, architects, landscape architects, infrastructure engineers, and more. What will it take to achieve the change that we need?

Looking at cities holistically

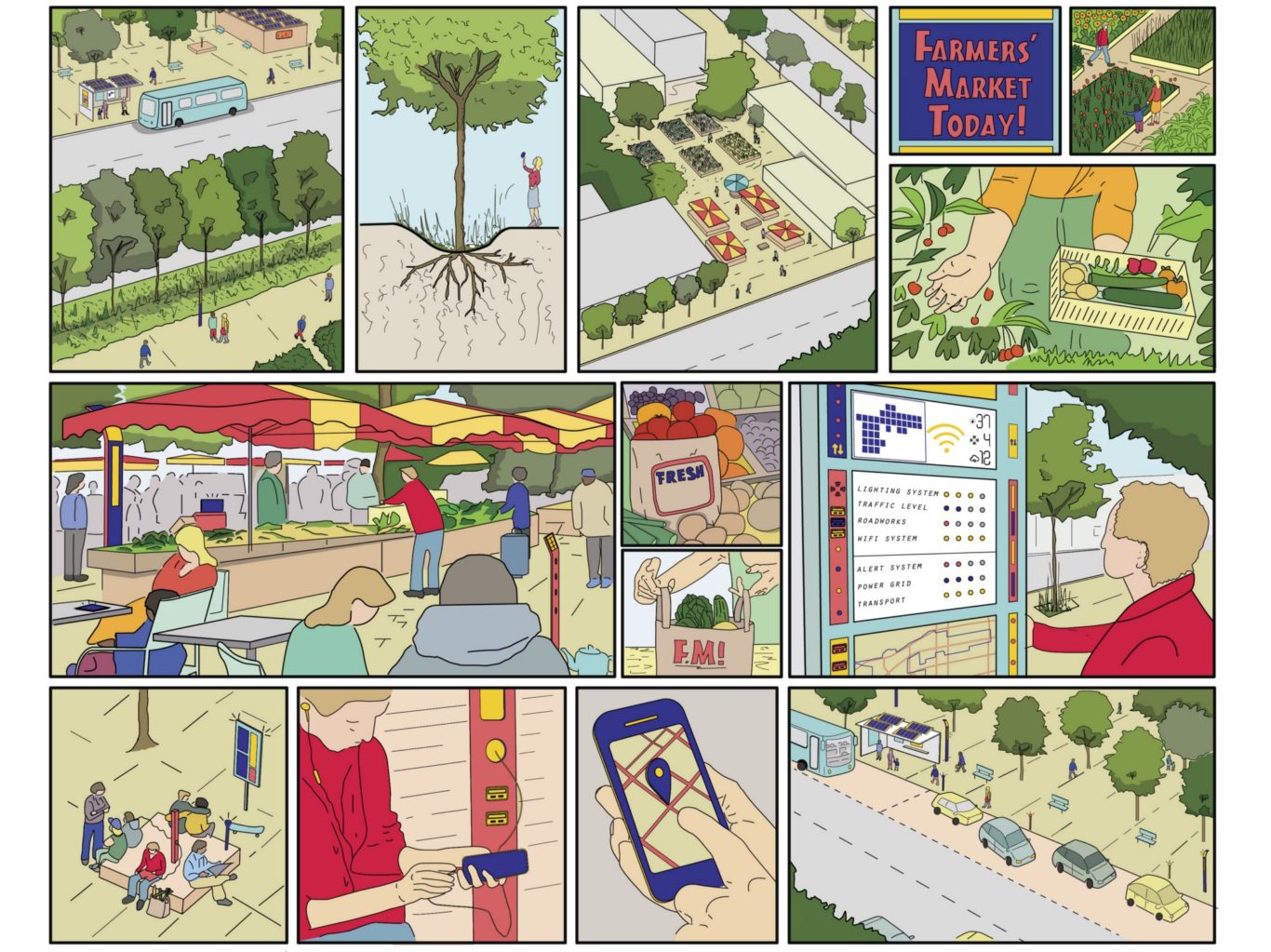

To fully address the challenge, we must look beyond individual buildings: it takes more than sustainable structures to make a resilient city. It also requires rethinking transit infrastructure, energy production, industry, and more. On top of this, we’ll need to address new challenges that are emerging due to the climate crisis — including sea level rise and extreme weather events.

Cities are very complex organisms. We have to consider not just built structures — roads, infrastructure, buildings — but also the natural environment, economic resiliency, social equity, and cultural history. City planners and architects don’t have all the answers. We need to start a broad dialogue with experts from many fields, and work together to invent solutions.

Three key areas have enormous potential to transform the sustainable impact of cities: energy, transportation, and technology.

How will clean energy transform cities?

By shifting from fossil fuels to clean energy sources, cities can dramatically reduce their carbon emissions. We can look to encouraging examples of cities that are leading the way. A number of urban areas are already operating on 100% renewable energy. These are mostly smaller cities — places like Basel, Reykjavik, and Burlington, Vermont — but they set an example for others to follow. Meanwhile, dozens of cities worldwide, including many of the largest in the UK, have made commitments to run on clean energy by 2050.

But clean energy is not the “silver bullet” to reducing cities’ carbon footprint — it’s only part of the solution. We have to fundamentally rethink how we use energy, and the sources it comes from. Strategies like net-zero design suggest a way forward. This type of thinking can be applied to a wide variety of projects — from public schools to dense, mixed-use city districts.

New, large-scale urban development projects could implement even more progressive measures beyond net-zero. If a majority of new developments can aspire to become “net-positive” and produce more energy than they consume, this could help overcome deficiencies elsewhere, and allow cities and nations to reach key targets more rapidly.

How should we reinvent urban transit?

Transportation accounts for the largest share of fossil fuel energy use in cities, globally. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Shenzhen set a benchmark in 2017 by becoming the first city in the world to run its entire bus network — a fleet of 16,000 vehicles — on electricity. The impact has been dramatic: the city has reduced overall emissions, improved air quality, and met its 2020 target three years early. London, New York, and other major cities are introducing electric bus pilot programs, with pledges to go all electric within the coming decades.

Autonomous electric vehicles (A-EVs) seem to promise sweeping changes to the very nature of the city itself. Because these vehicles could be used more efficiently, they open up the opportunity to reclaim urban space for any number of other uses — an idea we explored in a design study for repurposing the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in New York City as a green corridor for people and nature.

Employing efficient forms of “microtransit” is another strategy that deserves attention. Small, energy-efficient shared vehicles can fill in the “last mile” mobility gaps between mass transit systems, providing more options for mobility while reducing a city’s overall carbon footprint. By creating finer-grained networks throughout extended regions, suburbs can become more sustainably connected to the urban core, while traditional city centers can be reinvented. Our studio recently explored the potential of these ideas and more in a study for the City of London. By encouraging walking, cycling, and shared microtransit, we could reduce emissions, improve air quality, relieve congestion, and reclaim street space for people.

Holistic urban design can tie all of these threads together into a complete, coherent vision.

How will we define the “smart city”?

This term has been claimed and defined by tech companies, but its possibilities are so much greater than simply applying a layer of IT over the built environment and mining the data it produces. We should be helping to define the parameters of how such data is used. How might networked infrastructures — from sophisticated environmental sensors to the common cellphone — help urban citizens better understand their individual consumption patterns? How can the “intelligence” gathered from smart city technologies help designers better understand the environmental impacts of a building envelope or site plan? Beyond making cities run more efficiently, all of this should be aimed at enhancing natural systems and quality of life.

The responsibility for harnessing this information falls on the shoulders of both citizens and city leaders. Data can help us measure and understand the individual and collective impacts of energy use — and this type of awareness can influence decisions and empower individuals to embrace their role in creating a more sustainable future.

We’re all in this together

A blurring of boundaries is taking place across the design professions. We must work to better understand global forces at play so that we may find new forms of collaboration. Building the cities of the future will require a coordinated effort across many fields — science and technology, government and private industry. In particular, designers will need to become both more responsive to priorities set forth by policymakers, and more active in helping to shape and advocate for policies that will enable the sweeping changes we need.

Holistic urban design can tie all of these threads together into a complete, coherent vision. We have to remember what makes a city truly great, and why we choose to live in cities in the first place. Cities are diverse places that provide a setting for chance encounters — places where people “rub shoulders” to learn from one another, drive innovation, and come together as a community. As designers, our role is to create environments where all of us can thrive — while securing the future of the planet that sustains us.

Dan Ringelstein, an architect and urban designer, leads SOM’s City Design Practice in London.