When Nathaniel Owings, one of the most prominent architects of the 20th century, wrote these words in 1969, it was long before sustainability was a buzzword, and before the threat of climate change was widely understood. An environmental activist as well as a business leader, our firm’s co-founder spoke to the profound responsibility that architects have to protect our planet’s limited resources. This conviction has guided our work since.

Civilizations leave marks on the Earth by which they are known and judged. In large measure, the nature of their immortality is gauged by how well their builders made peace with the environment.

Today, the climate crisis, more than ever, demands urgent action. As architects, engineers, and urban designers working on projects all over the world, we are in a position to do something about it. For half a century, SOM has been focused on the environmental impact of what we build. By harnessing research — from timber construction to digital design—we have redoubled our efforts to confront the impacts of climate change.

On the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, we want to take the long view of what has shaped SOM’s approach to sustainability and created some of the most environmentally progressive projects of our time. Together, they represent an array of possibilities for what designers can do to safeguard the future of our planet.

Building meets landscape

Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters, 1971

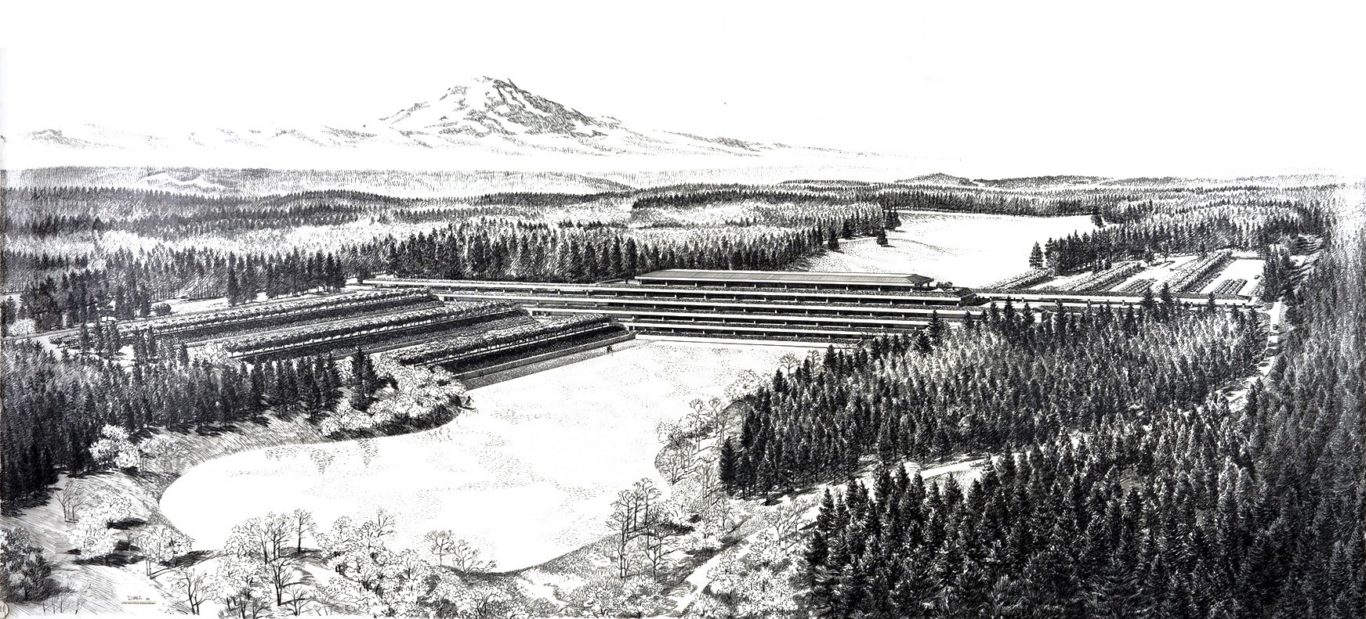

In 1970, the year that the first Earth Day demonstrations took place, SOM was at work on a project that would define ecological design at an unprecedented scale. Located on a verdant site in suburban Washington State, the Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters resembled no office building that had come before. SOM sought to integrate a single, vast building — with more than 350,000 square feet of office space — seamlessly into its bucolic surroundings. The result is a terraced, ivy-covered structure that seems to emerge from, and merge with, the landscape.

While most of the 260-acre site remained untouched, SOM worked closely with landscape architects Sasaki, Walker and Associates to find ways that the building could augment the landscape. Placed across a shallow natural creek, the structure essentially serves as a dam — transforming the creek into a small lake, and diverting the outflow toward a meadow to irrigate wildflowers and native grasses.

The building itself incorporates a range of sustainable strategies, including energy-saving heating and cooling systems that were highly innovative for the time. No less significant was the desire to elevate the everyday experience of Weyerhaeuser employees. Panoramic windows across every floor create a sense of immersion in nature — an experience of the building and its landscape that are one and the same.

Desert design reaches new heights

National Commercial Bank, 1983

As accelerating globalization yielded commissions in far-flung locales, Western designers had to confront the realities of building in diverse and challenging climate zones. One of SOM’s first projects in the Middle East is a key example. Lead designer Gordon Bunshaft considered the National Commercial Bank Headquarters in Jeddah “a totally new approach to solving an office building in an extremely hot and dry climate.”

Although Bunshaft is most often associated with International Style modernism, he understood the importance of designing a building that would respond to the climate and culture of Saudi Arabia. He looked to vernacular architecture and building methods for inspiration. Much like a traditional courtyard house, the 27-story bank tower is turned inward, in a V-shaped plan that encloses a central atrium. This natural ventilation shaft allows hot air to rise out of the building — a passive design strategy that greatly reduces the energy needed to keep the office floors cool.

The facades exposed directly to the desert sun are clad in travertine, while the shaded interior facades are clad in glass, offering spectacular views across the atrium toward the city and the Red Sea. Bunshaft’s design ingeniously reconciles Eastern and Western approaches to building. “Nothing could be more Western than a skyscraper,” MoMA curator Arthur Drexler remarked, “but Gordon Bunshaft’s rethinking of its nature for this site in Saudi Arabia seems to have resulted in a promising new type.”

A modern icon, restored

Lever House, 1952. Renovation, 2001

Renovation and adaptive reuse are increasingly important components of sustainable development — all the more so when it comes to landmark buildings. When Lever House was completed in 1952 in New York City, it became an instant icon, an emblem of modernity and progress. “It gave architectural expression to an age just as the age was being born,” the historian Reyner Banham wrote.

The 22-story tower, rising above Park Avenue with its glass and steel curtain wall, was the first of its kind in America. Lever House was indeed an experiment — and by the 1990s, the limitations of midcentury building materials and technology began to show. Water had seeped in behind the steel mullions, causing the carbon steel within the glazing pockets to rust and expand. This corrosion bowed the horizontal mullions and broke most of the spandrel glass panels. Only one percent of the original glass remained intact.

In 1998, developer Aby Rosen acquired Lever House, seeking to restore the building’s original glamour. He brought SOM back, nearly 50 years after the original design, to undertake a complete renovation. Drawing on five decades of expertise in facade technology, and working closely with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the team replaced the facade with a more resilient, state-of-the-art system that also maintains the integrity of the original design. Pristine once again, the new facade is designed to sustain the 20th-century landmark through the next century.

A lesson in sustainability

The Kathleen Grimm School for Leadership and Sustainability at Sandy Ground, 2015

Cities and nations around the world are focused on cutting carbon emissions. At the United Nations summit in September 2019, 77 countries, ten regions, and more than 100 cities committed to achieve net zero carbon by 2050. To reach this ambitious goal, city leaders will need to find new solutions to reduce energy use.

New York City aims to be ahead of the curve. In 2015, it opened a public school that is the first in the city, and among the first in the United States, to achieve net-zero energy — generating more energy than it consumes. The school, named The Kathleen Grimm School for Leadership and Sustainability at Sandy Ground, was initiated as a pilot project to test out a range of strategies that could lead to more energy-efficient buildings throughout the city.

The school’s cantilevered roof is covered in hundreds of photovoltaic panels, which convert solar energy into electricity. Passive design strategies were also key — the building is oriented to maximize natural light, and a system of windows and skylights reduces the need for artificial lighting for 90 percent of the day. Additional measures include a system of geothermal wells to naturally heat and cool the building, and a virtually airtight enclosure which helps maintain the indoor temperature. The design team also saw an opportunity to help educate the next generation in the lessons of environmental responsibility. For the school’s more than 400 students, the building itself is part of the curriculum.

Bruce Barrett, former vice president for architecture and engineering at the city’s School Construction Authority, describes the project as a springboard: “The amount of work was just enormous — but having taken the risk, and done the labor and the research, the payoff has been fabulous.”

Timber is the future

Billie Jean King Main Library, 2019

Concrete, steel, and glass dominate the modern cityscape — but natural materials, such as wood, offer advantages that are more relevant than ever. For a new timber-framed library in Long Beach, California, SOM sought to celebrate the qualities that make wood a sensible, sustainable, and aesthetically appealing choice for contemporary architecture.

“Our goal was to leverage the power of clear ideas, natural materials, and Southern California sunlight to create a bright, beautiful, and beloved new place for the people of Long Beach,” says design partner Paul Danna.

The new Billie Jean King Main Library, part of the complete redevelopment of the city’s downtown Civic Center, sits above an existing underground concrete parking garage. Timber was, first of all, a practical choice: by using this lightweight material, the new building framework could rest on existing columns of the garage. Saving most of the concrete structure allowed the design team to significantly cut down on material waste. Just as importantly, by using wood and the existing foundation, the design reduces embodied carbon by 61 percent, compared with erecting a new parking garage and a conventional concrete building.

The exposed timber structure is the library’s defining feature, inside and out. The beams frame a 39-foot-high atrium at the center of the building — a warm, inviting space, filled with natural light. The design takes advantage of the Southern California sun in another way as well: the expansive flat roof supports an array of more than 1,500 photovoltaic panels.

The design team considered the impact of materials even beyond the library’s eventual lifespan. The wood used to build the structure, comprising more than 80 percent of the building material, can be repurposed in the future.

Back to nature

The Wild Mile, ongoing

Cities around the world face the challenge to revitalize formerly industrial waterfronts. An ambitious effort in Chicago offers an example for how to reimagine an urban waterway for the next century: as a place where people and nature can thrive.

When completed, the Wild Mile will transform the human-made branch of the Chicago River into an “eco-park” with floating gardens, forested walkways, and kayak docks. More than a public amenity, the Wild Mile advances a community-led vision of renewed urban ecology that helps to connect neighborhoods, generate cleaner water, and support more resilient ecosystems.

In 2016, Urban Rivers and SOM installed a 1,500-square-foot floating garden as a first step in bringing the Wild Mile vision to life. Since then, the project has grown to involve multiple partners, including the City of Chicago, O-H Community Partners, Near North Unity Program, Omni Ecosystems, Tetra Tech, d’Escoto, Inc., and members of the local community. Shedd Aquarium has introduced the Kayak for Conservation program, allowing Chicagoans to paddle through this ecosystem, and Urban Rivers is installing the first floating pathway on the Wild Mile this summer.

Making the most of its proximity to more than 40 schools and academic institutions, the Wild Mile also incorporates rich educational and community programs. These include River Rangers, an initiative led by Urban Rivers which recruits “citizen scientists” to report on reintroduced plants and wildlife.

In many ways, the Wild Mile initiative brings to light the opportunities and challenges and that cities face in confronting climate change—issues that go beyond the scope of urban planning and design. Building a sustainable future is a deeply collaborative endeavor, rooted in local communities. All of us have a stake, and all of us must take part, in turning this vision into a reality.