The urgent need for shelter is often accompanied by a lack of resources. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, more than half of the urban population lives in substandard housing — a problem compounded by the fact that many families do not have access to conventional financing and building materials.

In places where resources are scarce, could a return to traditional building methods provide a solution for durable, low-cost construction?

That’s one of the ideas that has emerged from the Timbrel Vault Workshop — an annual event led by architects and engineers who are seeking to revive a building method that is centuries old, but seldom used today.

“Our goal was to re-evaluate an ancient and forgotten technique, and above all to demonstrate that it could be used on equal terms as any other current method,” says Julio Jesús Palomino, the architect who organizes the workshop in affiliation with the University of Alcalá. “It’s just necessary to find the right context and to use it intelligently and safely.”

Made with interlocking layers of brick or tile, timbrel vaults rely on the strength of masonry in compression. As a result, they are remarkably efficient: a slender arch can bear surprisingly heavy loads. With the right knowledge, these vaults can be easily constructed from inexpensive and local materials.

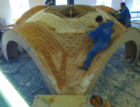

What also sets timbrel vaults apart is their self-supporting ability, even while being constructed. There’s no need for the formwork that’s required for other types of vaults, making them faster and less expensive to build. “It’s kind of magical to see people working on it,” says Alessandro Beghini, a structural engineer at SOM who contributed to the workshops. “At a certain point, the masons are standing on top of the structure that they’re actually building.”

Timbrel vault techniques have been used for centuries, and their versatility, strength, and expressive aesthetic qualities have given rise to works of architecture that continue to inspire people today. Antoni Gaudí, for example, relied on these methods to create several of his exuberant structures in Barcelona. The self-supporting vault made a notable debut in America in the late 19th century, when engineer Rafael Guastavino developed and patented a tile-arch system. For several decades, the “Guastavino vault” was used widely in the northeastern United States, including in major civic buildings such as Boston Public Library and New York City’s Grand Central Terminal.

Even in light of these architectural triumphs, timbrel vaults fell largely out of use by the mid-20th century, when reinforced concrete and steel construction became the norm. The team behind the Timbrel Vault Workshop is working to change that. Because of its advantages as a low-cost and sustainable building method, the organizers see great potential in places such as Africa, where communities could build vault structures with local, affordable building materials. Since 2016, the workshop has developed prototypes for schools and other structures in places such as Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Kenya.

Despite the vaults’ incredible strength in compression, they have a significant weakness: they are vulnerable to lateral forces, such as those caused by an earthquake. That’s why the workshop’s organizers first sought out SOM’s expertise. “The gravity loads of these structures are well known, because they’ve been using these structures in Europe for hundreds of years,” says SOM structural engineering partner Mark Sarkisian. “But when an earthquake comes, it’s a totally different ballgame.”

An international expert in seismic engineering, Sarkisian is best known for his work on skyscrapers. He was intrigued by the opportunity to design a more resilient timbrel vault, in part because it resonates with his research-driven work at SOM. “No matter the scale or the shape of what you’re building, the fundamental considerations are the same — finding the most efficient, economical, and resilient form,” he says.

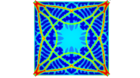

In 2017, the first year that SOM participated in the workshop, the team explored ways to reinforce the vaults using lightweight and low-cost materials. The team proposed wrapping the structure in geogrid, a synthetic mesh that’s readily available but not typically used for structural reinforcement. “We built computer models using the same commercial software and techniques that we use for our buildings — to demonstrate that this technique was actually going to improve the performance of the vault,” says Samantha Walker, who is part of the SOM engineering team.

Then, in collaboration with their colleagues at the workshop and the University of Alcalá, the group put their design to the test — comparing the performance of reinforced and unreinforced vaults using a shake table, a device that simulates the forces of an earthquake. The reinforced structure “turned out to be so strong that we couldn’t break it,” Beghini says. “Making it collapse was beyond the experimental capabilities of the workshop.”

SOM engineers joined the workshop again the following year, this time focusing on more efficient forms which could allow the vault to be lighter and therefore less expensive to build. “We wanted to find areas where we could remove material to lighten the vaults, but doing so in an informed way,” Walker says.

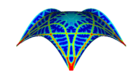

This year, the team found an opportunity to bring their work to a broader audience when Fundación COAM, an architectural organization in Madrid, hosted an exhibition on SOM’s structural engineering practice. Together with their colleagues in Spain, the SOM team designed a full-scale timbrel vault for the show, applying insights gained from several years of research. With a striking and unconventional design, the exhibition vault has a large opening in the center, which makes the structure lighter without sacrificing strength.

Now, the team is looking toward the next frontier: automated construction. It might not be far-fetched to teach a robot how to build a vault, Mark Sarkisian says, and the applications could have a big impact. “With automated construction, you could imagine bringing these types of structures to developing areas that need shelter and need it quickly. Much like 3D printing, it could be almost like a ‘printed structure,’ made out of assembled blocks of material,” he says.

Now in their fourth year of working together, the international group of architects, engineers, and researchers has pushed each other toward new discoveries. “The collaboration with SOM has been a turning point in our work,” says Palomino. “It has put us in dialogue with ways of working and a level of excellence in design and detail that has raised the bar of our work.”

As climate change makes sustainable construction an urgent priority everywhere — not just in developing countries — the workshop could lead to new solutions for bigger building projects. “We might discover a construction technique that everyone might use someday for large-scale construction,” Sarkisian says. “So that’s our hope — that we work through the fundamentals, and then create something conceptually much larger.”

Timbrel Vault Workshop team

Julio Jesús Palomino, architect

Manuel Fortea Luna, architect and professor, Universidad de Extremadura

Rosa Cervera Sardá, architect, professor and director of the Master of Architecture program, University of Alcalá

Antonio Sousa Gago, engineer, Instituto Superior Técnico de Lisboa

Rafael Casas Mayoral, architect