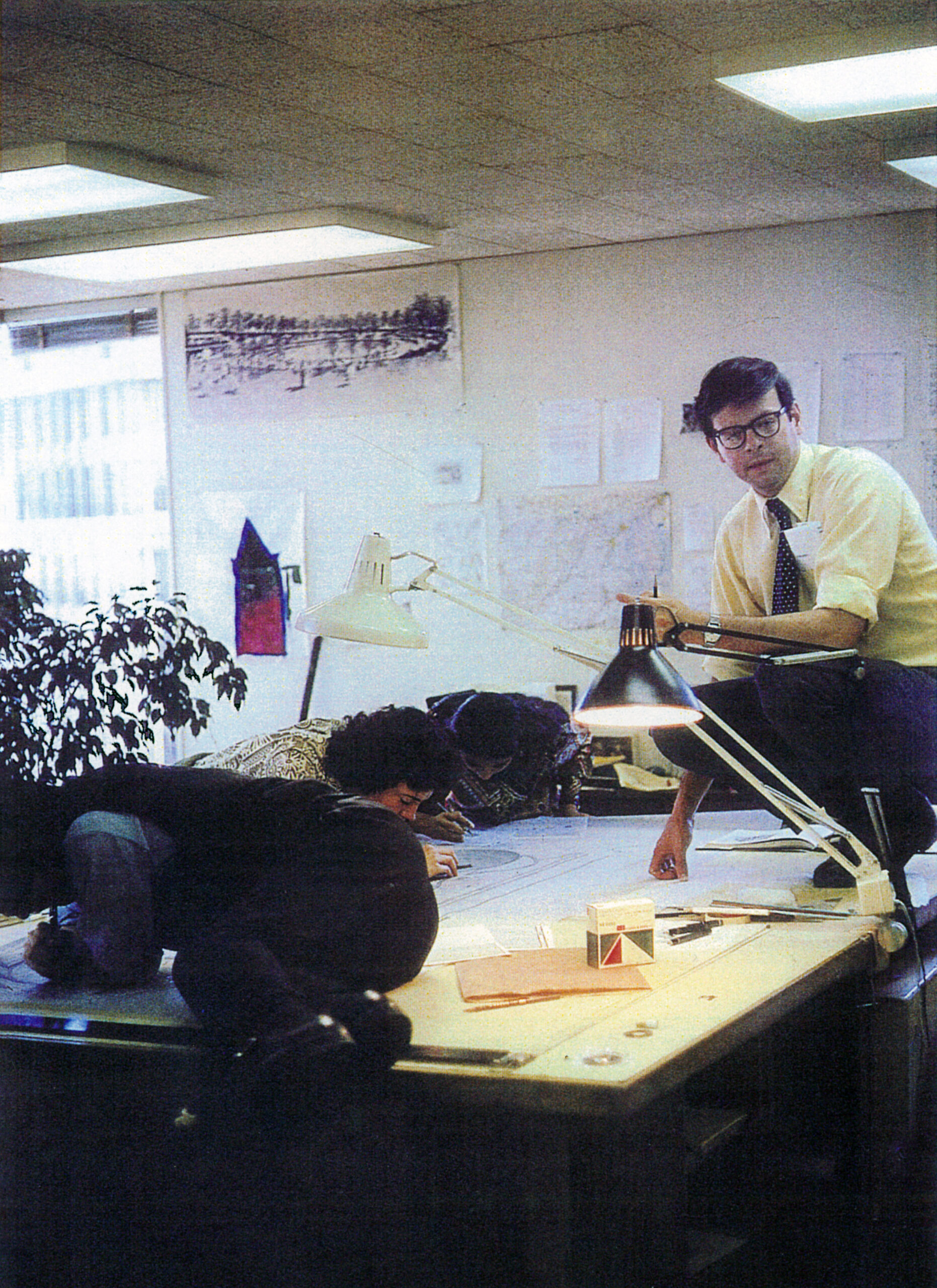

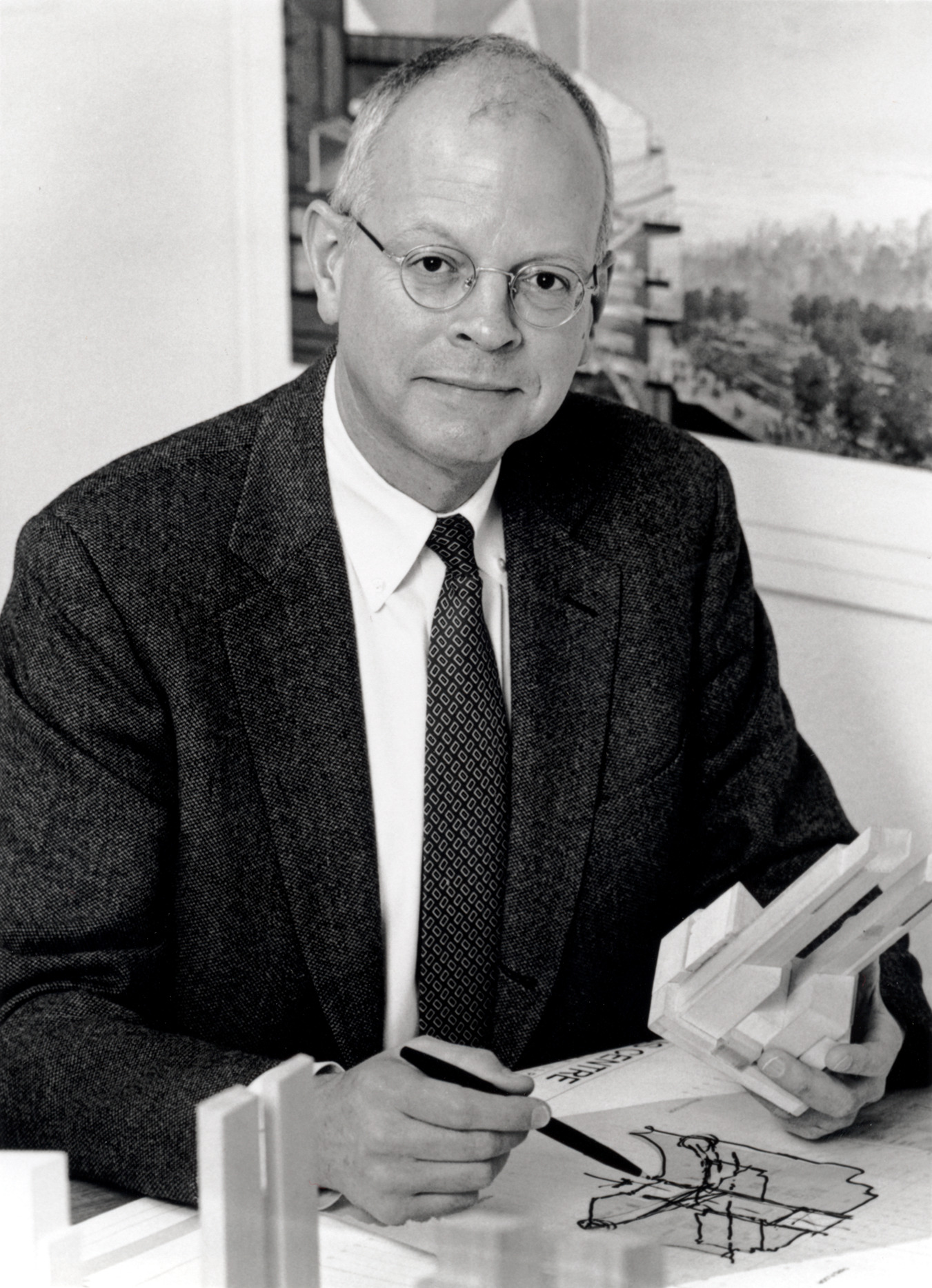

David M. Childs, FAIA, touched countless lives through his leadership at SOM and his work around the world. Since his passing on March 26, we have been reflecting on his 50-year career—from his work on some of the most complex projects in the firm’s history to the era of growth he ushered near the turn of the century.

David had an outsize impact on the New York City skyline, Washington, D.C.’s downtown, and cities across the world. Often in the public spotlight, he led the design of many of New York’s highest profile projects, including One World Trade Center, One Worldwide Plaza, and the Time Warner Center (now Deutsche Bank Center) at Columbus Circle. In the nation’s capital, his master plan for Constitution Gardens transformed a vast portion of the National Mall into a pedestrian-centered public park, and his work in transportation—from expanding Toronto Pearson International Airport to fostering the creation of Moynihan Train Hall in New York—dramatically improved the travel experience in some of the world’s busiest transit hubs.

David had an outsize impact on the New York City skyline, Washington, D.C.’s downtown, and cities across the world. Often in the public spotlight, he led the design of many of New York’s highest profile projects, including One World Trade Center, One Worldwide Plaza, and the Time Warner Center (now Deutsche Bank Center) at Columbus Circle. In the nation’s capital, his master plan for Constitution Gardens transformed a vast portion of the National Mall into a pedestrian-centered public park, and his work in transportation—from expanding Toronto Pearson International Airport to fostering the creation of Moynihan Train Hall in New York—dramatically improved the travel experience in some of the world’s busiest transit hubs.

David’s legacy is defined by these building projects, but also by his influence as an inspiring leader and mentor to generations of architects at SOM.

“He had such a profound impact on our lives,” said Partner Laura Ettelman, who serves on SOM’s Executive Committee. “We’ve had a lot of towering figures in SOM’s history, but few have had the kind of impact that David had. He was a visionary and cared deeply for the people he worked with and designed for, and that compassion came through in everything that he did. He saved our firm in the economic downturn of the 1990s, developed new areas of practice, and heralded an urbanistic design approach that persists across all our work today.”